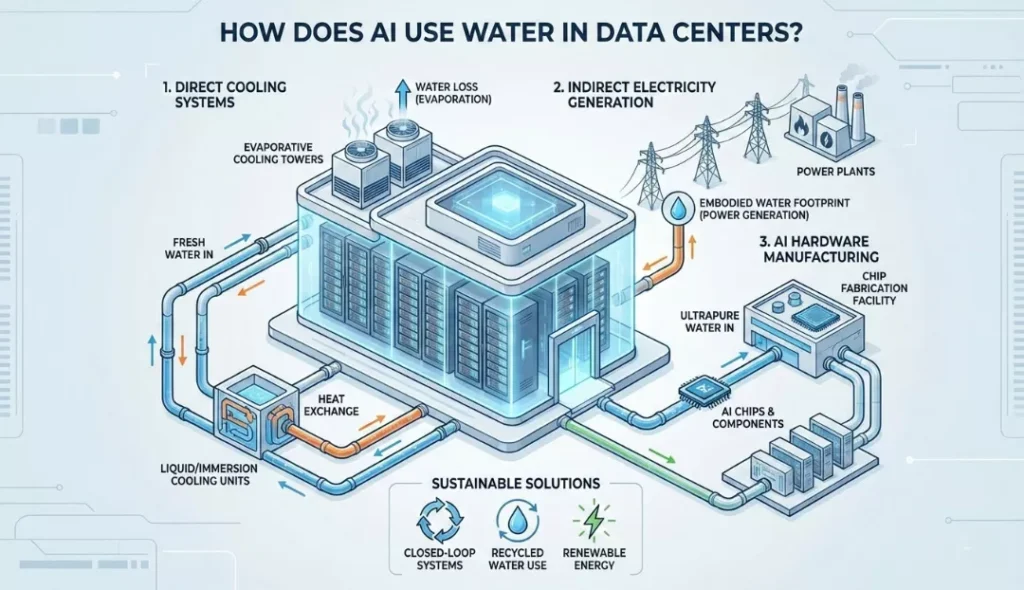

AI primarily consumes water through direct evaporative cooling to prevent high-performance servers from overheating. Additionally, it relies indirectly on the massive water requirements of power plants that generate the electricity AI requires. As models like GPT-4 or Gemini perform complex calculations, their Graphics Processing Units (GPUs) generate intense heat. Consequently, data centers utilize “cooling towers” that evaporate fresh water to chill the air—essentially making the data center “sweat” to stay cool. This process permanently removes water from local supplies. Furthermore, recent 2026 estimates suggest that for every 20 to 50 prompts you send to an AI, the system “drinks” approximately 500ml (16 oz) of water.

Key Highlights

- The Hidden “Thirst”: AI does not just consume electricity; it actively consumes massive amounts of water primarily through evaporative cooling systems and indirectly through power plant cooling.

- The “Bottle” Metric: Research indicates that a standard conversation with an AI chatbot (roughly 20–50 questions) consumes approximately 500ml (16 oz) of fresh water.

- Training vs. Inference: While training a model represents a significant one-time water cost (e.g., 700,000 liters for GPT-3), the daily usage by millions of users (inference) accounts for the vast majority of long-term water consumption.

- Geographic Strain: Companies often locate data centers in regions with cheap energy but high water stress (like the American Southwest). As a result, this leads to potential conflicts with local communities and farmers.

- Efficiency Shift: To combat this, the industry is moving toward liquid cooling (direct-to-chip) and “Water Positive” goals, aiming to replenish more water than they consume by 2030.

The Thermodynamics of AI: Why Data Centers Are So Thirsty

Data centers act as the physical “brains” of the internet, housing thousands of server racks. In the era of Generative AI, operators pack these servers with high-performance chips (like NVIDIA H100s) that run 24/7.

When electricity flows through these chips to perform calculations (matrix multiplications), it encounters resistance. This process converts electrical energy into thermal energy (heat). If operators do not remove this heat immediately, the chips will throttle (slow down) or physically melt. Therefore, data centers employ one of several cooling methods, with evaporative cooling remaining the most water-intensive.

The Two Types of Water Consumption

To understand the impact, we must first distinguish between two key metrics:

- Water Withdrawal: Taking water from a source (lake, river, aquifer) and returning it later (often warmer or with chemicals).

- Water Consumption: Water that the system removes from the source but does not return because it evaporated into the atmosphere. This represents the primary concern for AI sustainability.

Cooling Technologies: From Air to Liquid

The method a data center uses to cool its AI servers directly dictates its water usage.

1. Evaporative Cooling (The “Swamp Cooler” Method)

This remains the industry standard for many hyperscale data centers because it is energy-efficient, even though it is water-inefficient.

- How it works: Fans pass hot air from the servers over wet pads or through a cooling tower where sprayers apply water. Subsequently, the water evaporates, absorbs heat, and cools the air, which the system then recirculates to the servers.

- The Cost: This process consumes pure, fresh water. As water evaporates, it leaves behind minerals (calcium, magnesium) that can clog pipes. To prevent this, data centers must periodically flush out the mineral-heavy water (called “blowdown”) and replace it with fresh “makeup water.”

2. Liquid Cooling (The High-Performance Method)

As AI chips get hotter, air cooling becomes insufficient. Consequently, liquid cooling is rising in popularity.

- Direct-to-Chip: Pumps circulate coolant directly to a cold plate sitting on top of the GPU/CPU.

- Immersion Cooling: Operators submerge the entire server rack in a non-conductive dielectric fluid.

- Water Impact: These systems usually operate as “closed loops.” Therefore, they consume significantly less water on-site than evaporative towers, though they require specific infrastructure.

Quantifying the Consumption: Training vs. Inference

AI water usage occurs in two distinct phases: Training (teaching the model) and Inference (using the model).

Training: The Upfront Cost

Training a massive model like GPT-3 or GPT-4 involves running thousands of GPUs for weeks or months.

- Statistic: Research estimates that training GPT-3 alone directly consumed 700,000 liters of fresh water—enough to fill a nuclear reactor’s cooling pool.

- Scope: This figure only accounts for on-site cooling. However, if we include the water used to generate the electricity (Scope 2), the number triples.

Inference: The Ongoing Cost

In contrast to training, which is a one-time event, inference happens every time a user asks a chatbot a question.

- The “Bottle” Metric: Studies suggest that a conversation with ChatGPT (roughly 20–50 questions) consumes approximately 500ml (16 oz) of water.

- Scale: With hundreds of millions of daily active users, the aggregate water consumption of inference dwarfs that of training over time.

Recent Statistics: The Scale of the Issue

The table below highlights the estimated water impact of major AI activities and company footprints using late 2024/2025 data analysis.

| Metric | Estimated Water Consumption | Context |

| GPT-3 Training | 700,000 Liters | Equivalent to the daily water footprint of ~2,000 average Americans. |

| ChatGPT Conversation | 500 Milliliters | Per 20-50 queries (approx. 1 standard water bottle). |

| Google’s 2023 Total | 6.4 Billion Gallons | A significant portion is attributed to data center cooling for AI ramp-up. |

| Hyperscale Facility | 1 – 5 Million Gallons/Day | A single large data center can use as much water as a town of 10,000–50,000 people. |

| Global AI Projection | 4.2 – 6.6 Billion $m^3$ | Projected annual water withdrawal by AI in 2027 (roughly half of the UK’s total annual withdrawal). |

Note: These figures are estimates based on academic research and corporate sustainability reports. Furthermore, “Scope 2” (indirect water from electricity) varies heavily by region; for instance, a data center powered by solar panels uses far less water than one powered by coal or nuclear.

The Environmental and Social Impact: The AI “Water vs. Watts” Dilemma

As the AI revolution accelerates in 2026, the industry faces a crossroads known as the “Water vs. Watts” tension. To achieve the high electrical efficiency (low PUE) that modern standards require, many data centers have historically leaned on evaporative cooling. However, this saves electricity at the direct cost of local water supplies—a trade-off that is increasingly under fire.

1. Local Water Stress: The Front Lines of AI Expansion

Companies often strategically place data centers in regions like Arizona, Texas, and Northern Virginia because of tax incentives and existing fiber networks. Unfortunately, these represent the same regions facing historic droughts.

- The Texas Surge: In 2025/2026, Texas has seen a massive influx of AI projects, including the “Stargate” AI supercomputer campus. Projections suggest that by 2030, data centers could consume up to 7% of all water in Texas—roughly 400 billion gallons annually.

- Community Conflict: In areas like San Antonio and parts of Arizona, officials have asked residents to restrict water usage (shorter showers, lawn bans). Meanwhile, local data centers continue to “guzzle” millions of gallons daily. This discrepancy has sparked “water wars,” leading to new calls for legislative caps on industrial water withdrawal.

- The “Feedback Loop”: Climate change creates record heatwaves $\rightarrow$ AI chips run hotter and need more cooling $\rightarrow$ Data centers evaporate more water $\rightarrow$ Local water levels drop, further straining the environment.

2. Water Usage Effectiveness (WUE): The New Gold Standard

While energy efficiency defined the focus of the 2010s, WUE is the metric defining the 2020s.

$$WUE = \frac{\text{Annual Site Water Usage (Liters)}}{\text{IT Equipment Energy Usage (kWh)}}$$

- Current Benchmarks: While the global average remains near 1.8 – 1.9 L/kWh, 2026 industry leaders are achieving stunning results. Microsoft, for instance, reported a WUE as low as 0.03 L/kWh in some European facilities by using advanced air-cooling and liquid-to-chip designs.

- The Regulation Shift: Starting in early 2026, new regulations in regions like the EU now mandate that data centers above a certain size report their WUE transparently. Consequently, this forces companies to move away from “wasteful” open-tower cooling.

Solutions: The Blueprint for “Water Positive” AI

By 2030, Big Tech aims not just for “neutrality” but to be Water Positive—meaning they return more water to the ecosystem than they take. Here is the 2026 roadmap for that transition:

- A. Membrane & Adiabatic Cooling (The “Smart” Cooler): New for 2026, Membrane Liquid Cooling works like a “Gore-Tex” layer for data centers. It allows heat to escape as vapor through a microscopic membrane while keeping the actual liquid water trapped inside for recycling. Therefore, this technology can reduce on-site water loss by up to 90%.

- B. Switching to Non-Potable Water: Companies are investing in “Purple Pipe” infrastructure to use greywater (treated sewage/industrial wastewater) for cooling. For example, Google’s 2025/2026 sustainability portfolio includes over 100 projects aimed at utilizing recycled water, ensuring they do not compete with residents for drinking-quality water.

- C. “Follow the Moon” Workloads: AI computing does not need to happen in one fixed location. Using Carbon and Water-Aware Software, companies now dynamically shift massive AI training “jobs” to regions where the air is naturally cool (like Norway or Ireland) or where the local water table is currently overflowing due to seasonal rain.

- D. Direct-to-Chip & Immersion Cooling: Operators are replacing traditional fans. In Direct-to-Chip (DTC) systems, engineers bolt cold plates directly onto the processors. Even more advanced is Immersion Cooling, where servers sit submerged in a vat of special non-conductive liquid. Since these act as “closed loops,” the water used to cool the liquid never evaporates—it simply stays in the pipes.

Conclusion

AI does not physically “drink” water, but its infrastructure maintains a massive, hidden thirst. As we integrate AI into every aspect of our digital lives, from search engines to video generation, the physical cost of that processing power becomes a critical environmental issue. While the efficiency of cooling technology is improving, the sheer explosion in demand for AI compute currently outpaces these gains.